Recession Risk Indicator: Yield Curve Or Inflation?

The US Yield Curve

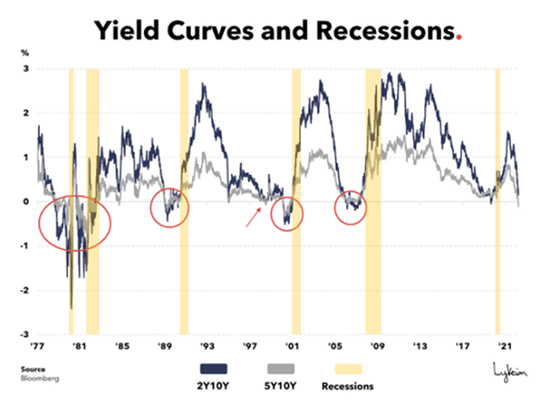

Every recession over the last 40 years has been preceded by an inversion of the US yield curve (circled below). Therefore, when this portion of the yield curve approaches zero, alarm bells often start ringing, and media headlines about recession risk explode.

There are many yield curves to consider, but the most widely used ones tend to be the 5y10y and the 2y10y. The former has already inverted and the latter currently sits around 0.15% above zero (close to a potential inversion).

An inversion, however, is usually only the beginning of a lengthy countdown to a recession. Furthermore, whilst every recession has indeed been preceded by an inversion, not every inversion has preceded a recession (1997 – red arrow above).

The first instance of an inversion can take place from months to years in advance of a recession taking place. The sequencing is usually:

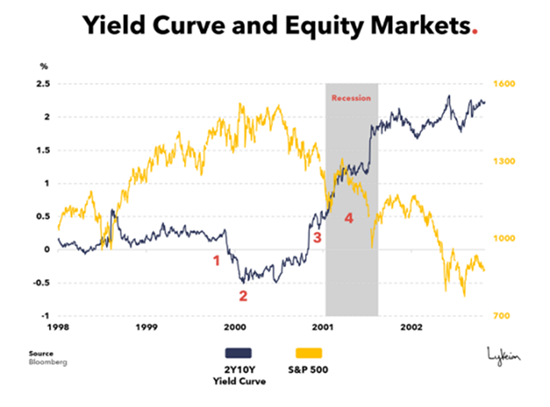

- The inversion begins, which is usually not particularly threatening to equity markets (1)

- The inversion continues until it reaches its maximum (lowest) point, which is generally when stock markets also peak, give or take (2)

- A re-steepening of the curve (2-Year Yields fall back below 10-Year yields), followed by a stock market sell-off (3)

- Somewhere between 6-9 months after, an economic recession begins (4)

An inversion is therefore a very poor timing tool for both recessionary events and peaks in the equity markets. And, as we all know, timing is incredibly important in the world of investing, as being “too early” is of no difference from being wrong.

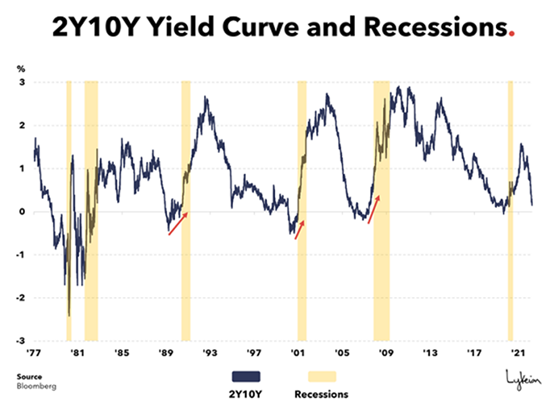

Remember: the prelude to a recession since the early 1980s has not been the yield curve inversion (there were a couple of small inversions not followed by a recession), but rather the re-steepening of the curve after a yield curve inversion.

This is largely down to the central bank’s reaction function:

- Over the last few decades, a typical boom-to-bust cycle has started with a pick-up in growth that allows central banks to raise rates.

- These higher rates track the higher growth until interest rates eventually reach a level where they start to hurt growth (the cost of capital exceeds the return on capital).

- This is usually where the inversion begins taking place - higher short-term rates (driven by central banks) and lower long-term rates (reflecting the expectation of slower future growth) drive the inversion (short term yields higher than longer-term yields).

A consequence of these higher short-term rates slowing growth (and driving long term yields lower) is that, after a period of prolonged below-trend growth, central banks will begin to cut rates to get the economy back on track. This cut to rates drives short-dated yields lower at a faster pace than longer-dated yields, which steepens the curve (short-term yields moving back to lower than long-term yields), usually in advance of the economy entering recession (red arrows below highlight the re-steepening of the yield curve ahead of a recession).

Ok, now you know what matters (re-steepening after the inversion) and why (central banks' reaction function slowing down growth).

So where are we currently in this process?

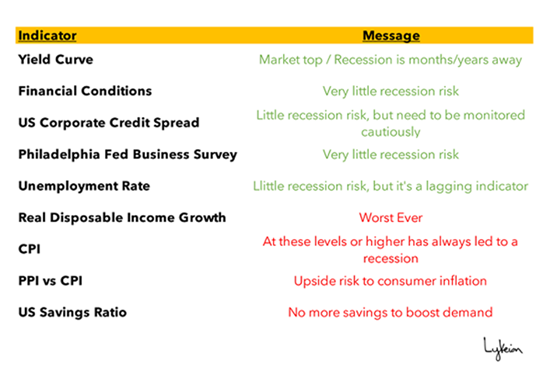

As of today, the yield curve has not even inverted, let alone re-steepened. Does that mean we are at least 6 months, if not further, from a potential recession? Maybe. On the face of it, other data points would suggest that no recession is imminent.

Financial Conditions, Credit Spreads, and the Consumer

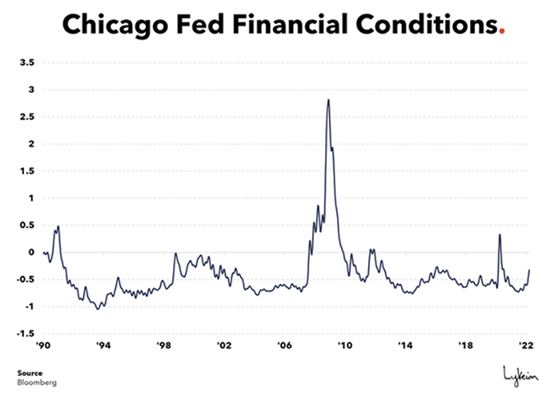

Financial conditions are getting tighter, but they are still low (or loose) and a long way from the spikes of 2008 and 2020.

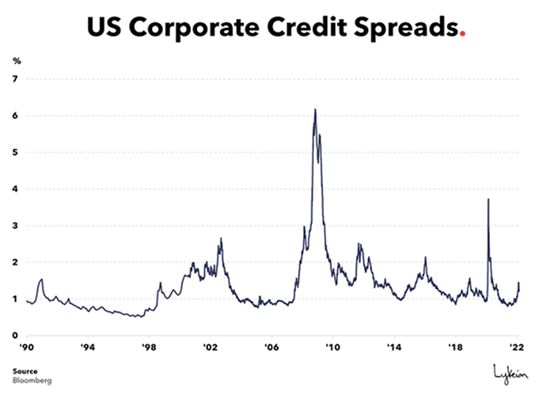

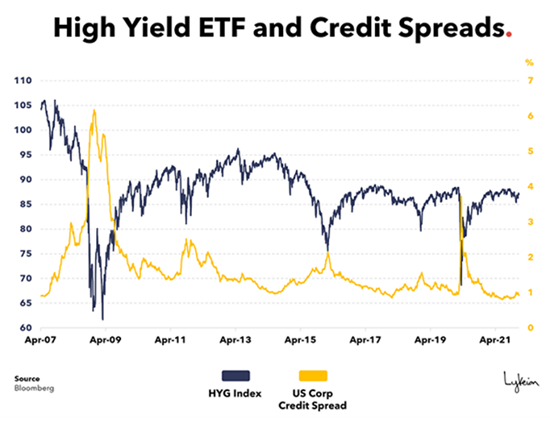

US corporate credit spreads (the difference between the yield on corporate bonds and government bonds) are widening (i.e. is getting larger), reflecting an increase in the perceived risk of default within the US corporate sector. But again, these wider credit spreads fall well short of 2020 and even the ‘2015 Profits Recession’ (the first time since 2009 that S&P 500 profitability fell in back-to-back quarters).

Spreads matter because credit is one of the main transmission mechanisms for the economy - credit growth helps to fuel economic growth (up to a point, according to Lacy Hunt).

A recession appears unlikely unless credit spreads significantly widen to the point where the cost of new credit becomes too expensive, causing credit-driven growth (which is most all growth) to slow. And whilst the credit market is not pricing in significant recession risks yet, we need to stress that, over the last decade, ending QE, beginning rate hikes, and rolling off the balance sheet would have taken four or five years – but this may now happen in a matter of months.

As such, credit spreads need to be monitored regularly.

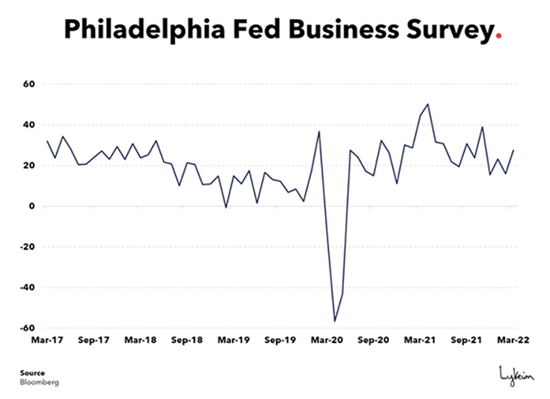

Furthermore, most of the business surveys are also in expansion territory, with some showing renewed strength in recent weeks.

There is very little within the corporate sphere which suggests undue stress in the system or an imminent recession. Many data points within the consumer sector also appear to be robust. US unemployment rates are close to their pre-pandemic levels - although jobs are a lagging indicator and prone to significant revisions.

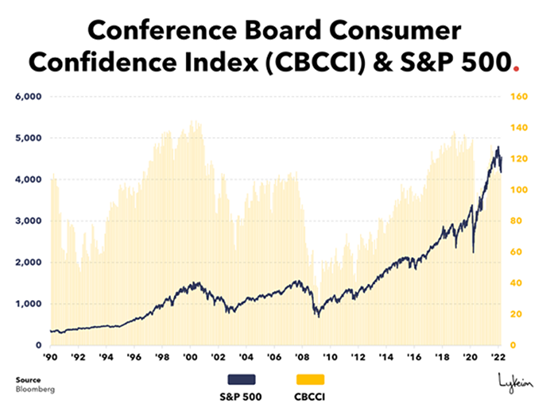

The Conference Board Consumer Confidence Index (a monthly survey of consumer attitudes, spending plans, and expectations for inflation, stock prices, and interest rates) is also riding high. This indicator, however, has generally flowed with the performance of the equity market. This measure of consumer sentiment is really a coincident indicator of the stock market.

So, in summary, the yield curve and other economic indicators are sending a message that we’re months away from an equity market top, and further away from an economic recession.

But could it be that all of these indicators are late in flagging the real risk of a recession? And if so, why?

Inflation Could be the Leading Indicator This Time

Whilst the above data is still not showing it, consumers are facing a significant headwind.

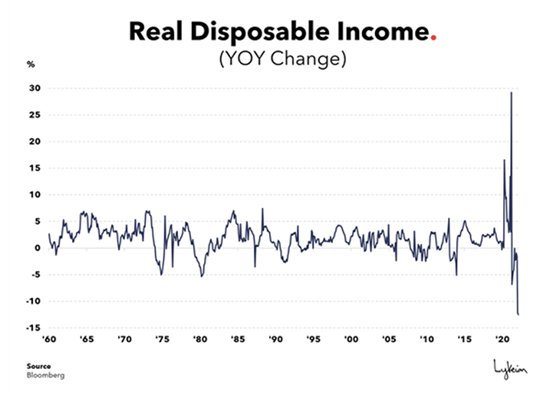

Wages may be rising, but they are not rising as fast as inflation. Real disposable income growth has never been worse - this includes the 1970s era of higher inflation.

Price increases have been dramatic, with US CPI rising from zero to nearly 8% in a few months. Wages have not had time to adjust, and there is no guarantee that corporates will hurt their margins by raising wages any time soon.

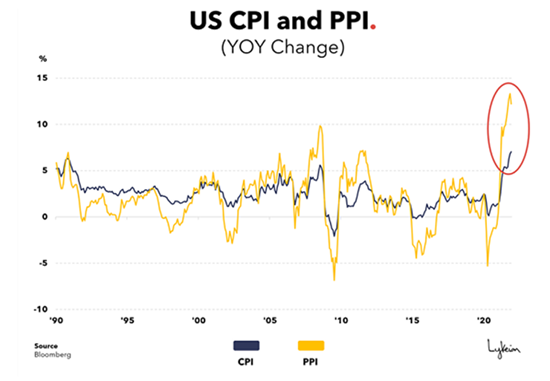

CPI is at its highest level in three decades, but, despite that, it still lags the rise in PPI (producer’s inflation, a proxy for the rise in cost of goods for businesses). These rises took place before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, meaning that the risks to PPI, and subsequently to CPI, despite already being at significantly high levels, remain to the upside (especially in Geopolitically sensitive areas like Oil and Food prices).

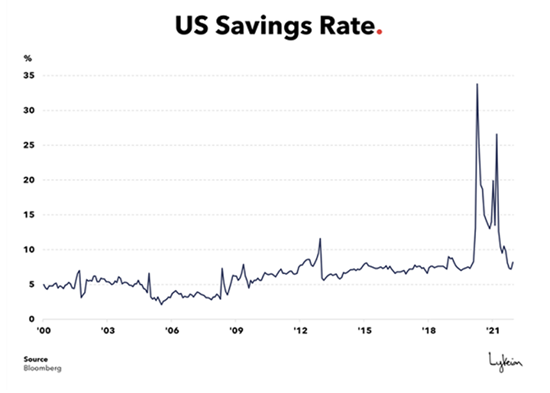

Meanwhile, savings ratios are starting to fall below pre-pandemic levels, as consumers supplement their declining real wages with savings in order to be able to spend at the same rate as before.

The consequence of this is that many consumers won’t be able to sustain the current level of demand – and in an economy like the US where 70% of the GDP comes from the consumer, this matters a lot.

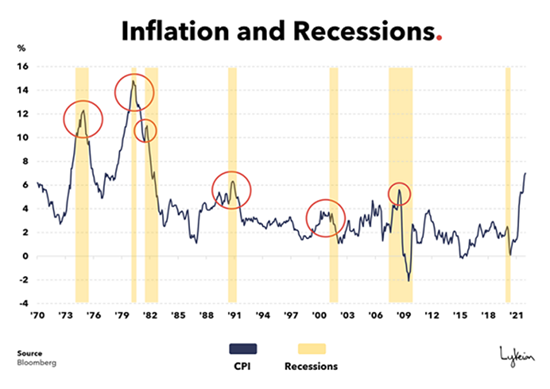

In fact, over the last 50 years, every time we had this level of inflation (or higher), the economy was about to enter or was already in a recession (except for the pandemic recession of 2020).

You don’t need peak inflation to enter a recession. Historically, inflation only peaks on the back of the slowdown it causes – i.e. it’s inflation’s impact on consumer demand that eventually starts a recession, and that same recession ends up slowing down inflation.

One very important thing to flag is the difference between how the yield curve and inflation are currently moving, and what that implies for recession risk going forward.

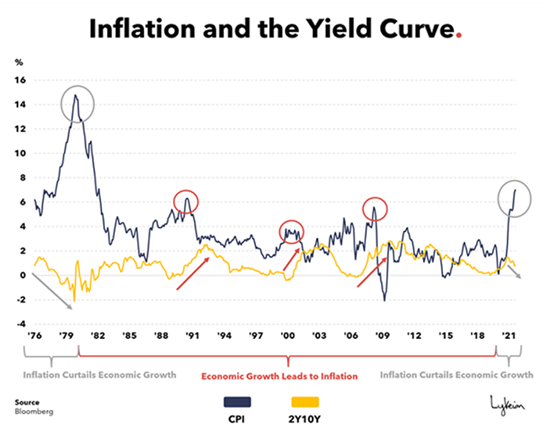

- Between 1980 and 2020, all inflation spikes (which were much lower than the current inflation spike) coincided with yield curves that were steepening (i.e. long-dated yields were moving higher at a faster pace than short term yields).

- That happened because, whilst you had inflation, you had higher demand driving actual economic growth, which forced longer-term yields to move higher.

- During this period, it was the economy that led inflation higher, and that’s why higher inflation was followed by a steepening of the yield curve (red arrows in the chart below).

But the opposite of that is happening today - we have higher inflation and a flattening (almost inversion) of the yield curve (grey arrows below), more similar to what happened in the 1970s.

Whilst the current period has many differences from the 1970s (there was a strong demographic backdrop and real wage growth), during the 1970s higher inflation was also destroying demand as it is doing today.

- Side note: The 1970s was a period of structurally high inflation due to a combination of factors that included high rates of population growth, supply-side shocks in the energy markets, and inflexible labor markets which were able to command significant price increases (the US labor market was far more unionized in the 1970s than it is today).

The difference between the 1970s and now, versus the period in between (1980s to 2020) is that for the latter, economic growth caused inflation, whilst for the former inflation is curtailing economic growth.

Why does this technical study matter?

Because if inflation today is demand destructive (like it was in the 1970s), then the yield curve sequencing we’re used to may actually be a lagging indicator – and we should instead use inflation as a recession risk indicator rather than anything else.

Lower Demand is the Only Antidote to Higher Inflation

Central banks are now caught between a rock and a hard place:

- If they don’t tighten, prices will rise at a faster pace and destroy demand, which will likely capitulate the economy.

- Even if they tighten, the impact on controlling inflation will likely be moderate as most of what we’ve seen has been driven by supply-chain issues (which central banks have little ability to solve).

Federal Reserve Chairman Powell has already hinted that interest rates may need to go up eight times this year. That would require a rate hike at every meeting in 2022 and at least one of them would need to be 50 basis points.

This is a very different dynamic from all the hiking cycles of the last 30 years. Credit spreads, whilst still moderately low, are starting to widen and the high yield ETF is rolling over. On all the previous occasions, when this happened, the Fed was either in or went into easing mode.

Today, the Fed is withdrawing support at the exact moment it previously used to add liquidity to the market. The current environment is nothing like we have seen over the last few decades.

It is our opinion that there is very little the Fed can do to rein in inflation, and that the only thing that can slow higher prices is the capitulation of consumer demand (end to the Russian invasion and an easing of supply chain bottlenecks would help as well…).

Whether because of high inflation or because higher rates might drive a financial markets meltdown (meaning that companies might start firing people and households would suffer negative wealth effects), lower consumer demand is the only real force that can slow down inflation.

Until that happens, we need to understand that we’ve entered a new paradigm. The old sequencing of the yield curve may now be obsolete, and a real slowdown could be on the near horizon despite the yield curve being months away from flagging any serious risk.

**********

Roger Hirst is Editor, Macro, at The Lykeion

***

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of AlphaWeek or its publisher, The Sortino Group

© The Sortino Group Ltd

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency or other Reprographic Rights Organisation, without the written permission of the publisher. For more information about reprints from AlphaWeek, click here.