The Case For Peak Hawkishness

Partner Content provided by The Lykeion

The ECB’s Pivot

For a full year, Christine Lagarde, President of the European Central Bank (ECB), actively refused to engage in conversations about the path of future monetary policy, despite the looming specter of higher inflation across the region.

That all changed in the first month of 2022 with her comments about the ‘normalization of our monetary policy’. It wasn’t a full-scale pivot to hawkishness of the Powell type in the second half of 2021, but it was enough for forward-looking European funding rates (EONIA) to explode higher.

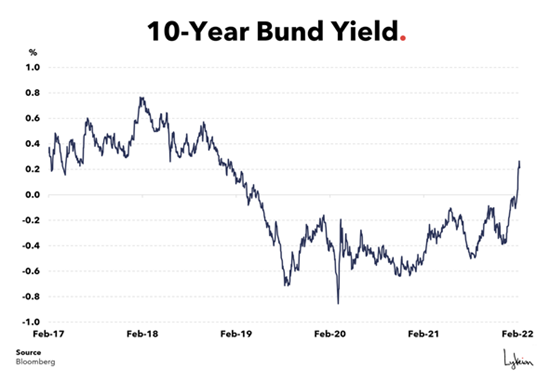

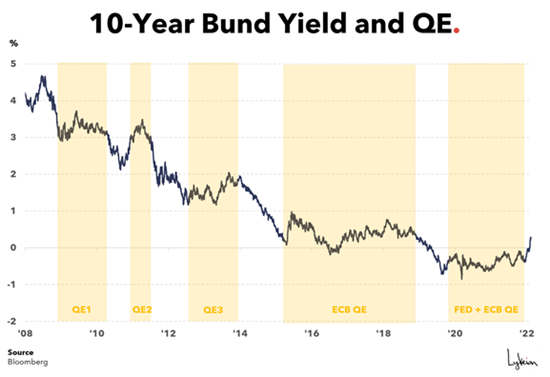

This led European yields to surge higher across all maturities. German 10-year (Bund) yields moved into positive territory for the first time since 2019.

For Europe, higher interest rates are a double-edged sword:

- Banks want higher yields to help improve their net interest margins (NIMs – the difference between what a bank receives and pays in interest) and therefore profitability, which in turn helps to pay down some of their debts.

- But, for many banks, their debts are so large that the gains in profitability are more than offset by the rise in financing costs implied by higher interest rates.

This is one reason why many investors think the ECB can never meaningfully raise interest rates, which also helps explain the surprise reaction at Lagarde’s sudden change of heart.

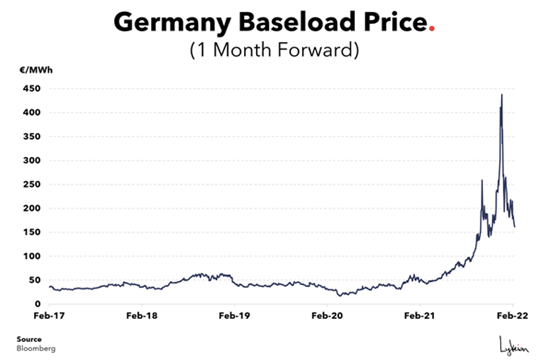

European inflation is also not the same as US inflation. The primary driver of inflation in Europe has been energy prices (and food), but core inflation has stayed relatively low:

- European energy prices have fallen more than 50% from their highs, but remain elevated. Underinvestment in traditional energy sources and the geopolitical tensions around the Nord Stream 2 pipeline will persist, but prices may have already peaked.

- Independently of this, there is very little that higher rates can do to address this specific problem, and more broadly speaking, it’s our stance that rates will have a minimal effect on exogenous geopolitical or supply chain related inflation (as we’ve highlighted in a previous Markets Update).

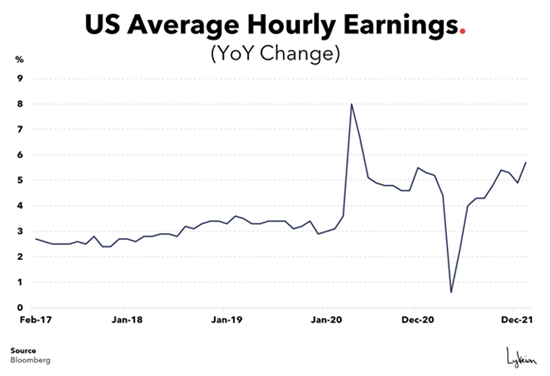

- European wage inflation, on the other hand, has remained relatively low, at about 2%, even while US wage inflation, measured as average hourly earnings, has headed toward 6%.

Therefore, the ECB (and the markets) may have performed a premature repricing of rates, reacting hawkishly to forms of inflation over which they have no control (supply-chain driven), at a time when global growth may be about to falter, something Tim has been tweeting about over the last few months.

The Case for Peak Hawkishness

The data points keep pouring fuel on the fire:

- The US CPI print exceeded expectations in January, coming in at 7.5% versus 7.3%.

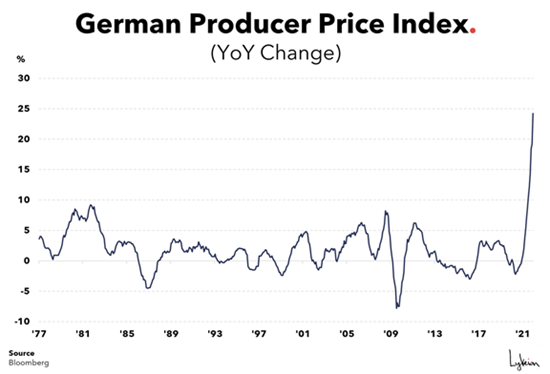

- German producer prices hit their highest level… ever.

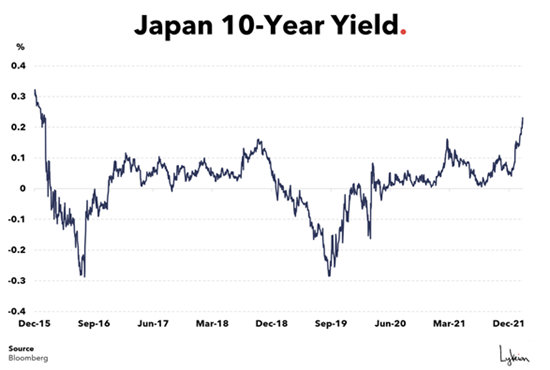

- US 10-year yields broke through 2% and Japanese 10-year yields reached their highest levels since 2016.

- After the US CPI print on February 10th, the Dec 2022 Fed Funds futures were implying US rates would be around 1.75% by year-end, which would entail 6 more hikes from current levels. (Note: Fed Funds futures work the same as other futures contracts (oil, gold, etc.), where the market forecasts where the rate will be on a certain future date).

Sell-side analysts have been falling over each other to revise their rate forecasts higher. Everyone thinks that rates and yields can only go in one direction, right?

Not necessarily.

We could be entering a period of peak hawkishness, especially if inflation and economic growth start rolling over.

Potential signs of peak inflation:

- Firstly, many of the year-on-year price comparisons from across the commodity complex will be falling in future months as higher comparative bases kick in.

- Secondly, the pandemic surge in goods consumption has likely peaked and will probably subside as restrictions are lifted and consumers substitute goods spending (staying in) with services spending (going out).

- Andreas Steno Larsen in his ‘Stenos Signals’ newsletter highlights an additional accelerator of this dynamic. The US CPI basket has changed, with the weighting of stay-at-home items increasing at the expense of going-out items. Therefore, when the substitution effect of consuming services instead of goods kicks in, it will amplify the decline in inflation (falling prices on a larger component of the CPI basket).

To be clear, we’re talking about the rate of change of inflation, not the level. The new, higher level in costs of goods, are likely with us for good, but the rate of change is likely to slow over time.

Potential signs of peak economic growth:

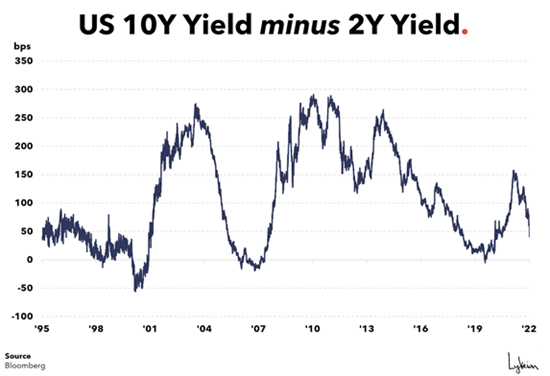

- If a flatter yield curve (flattening = the difference between the long end and the short end of the yield curve is getting smaller) is a sign of a weakening economy, then the rates market is screaming “there’s a slowdown dead ahead”.

- The difference between 10-year and 2-year yields is 40 basis points. If it continues to trade lower, one needs to be reminded that a decline to zero or under (an inversion) has preceded all the recessions since 2000.

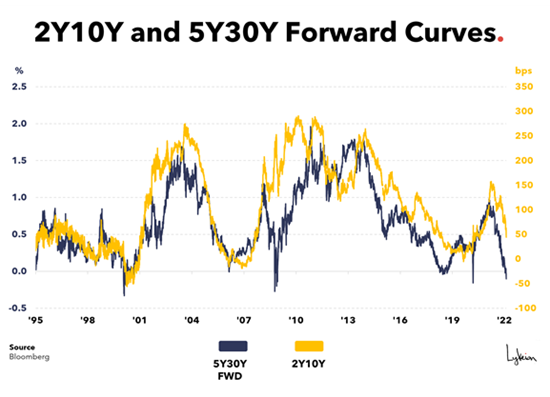

- If we really want to make the case for a yield curve inversion, we can find it in the 1-year forward version of the 5-year 30-year yield curve (this is looking 1-year out at the market's view of the 30-year less the 5-year yield).

- In full disclosure, there are so many different versions of the curve that we can almost always find a section that fits any narrative. But this forward curve has tended to lead the widely accepted 2-year versus 10-year yield curve, which has a great track record of inverting ahead of the last few recessions.

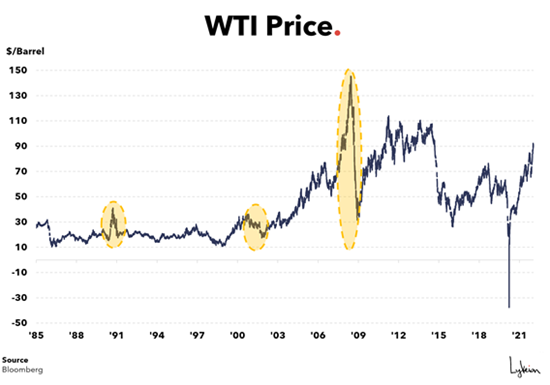

- Besides yield curves, high energy prices are also a drag on growth and have coincided with three of the last four recessions (the outlier being the exogenous shock of COVID).

- Inflation (if it remains elevated) is a significant drag if there isn’t sufficient growth to offset it.

- Related, whilst wages may be rising, real wages growth (adjusted for inflation) are still negative. This will be a drag on consumption.

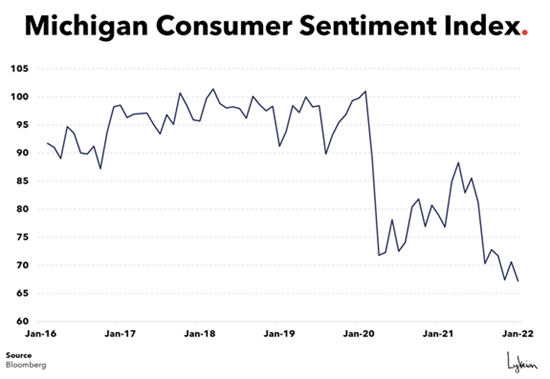

- Consumer sentiment today has fallen below where it was during the pandemic. The cost of large ticket items and the erosion of purchasing power is punishing the consumer.

- Tim’s Note: need another sign of peak economic growth? Ask Diego to send you some photos of his birthday bash last week at a Tuscan villa. We’re a bootstrapped startup and he somehow found a way to party like he was a member of the Medici clan for a weekend.

Ultimately, the key factor that leads us to believe that we may have reached peak policy is that almost everyone is now pricing higher inflation, higher growth and higher interest rates. This is THE narrative. It is what everyone expects. And what everyone expects, everyone rarely gets.

Sometimes you gotta zig when everyone else zags.

Consider this:

- If inflation is peaking and growth is rolling over, the Fed will be tightening into a slowing economy. Too much tightening will negatively impact risk assets (which are our favorite kind of assets).

- Slowing economies nearly always lead to lower levels of inflation.

- That double whammy will drive down growth and inflation, even though today’s inflation is more a problem of supply than demand, which interest rates have little ability to fix.

- The end of QE, counter-intuitively, has always led to periods of lower bond yields as the market moves ahead of Central Banks. QE is about to end in the US and, potentially, in Europe, so should we really be pricing in higher bond yields?

This is what peak policy hysteria looks like: pricing further economic growth, higher yields, and more inflation as we’re about to end QE and hike interest rates. We might see the market readjust itself to reflect this more dovish outlook soon.

**********

Roger Hirst is Editor, Macro, at The Lykeion

***

The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of AlphaWeek or its publisher, The Sortino Group

© The Sortino Group Ltd

All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or scanning or otherwise, except under the terms of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 or under the terms of a licence issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency or other Reprographic Rights Organisation, without the written permission of the publisher. For more information about reprints from AlphaWeek, click here.